‘osu?’ was a reversing challenge I wrote for BuckeyeCTF 2022.

- challenge.zip

- Source on Github (only made available after the CTF)

Introduction

Both Mac and Linux binaries were provided.

The README contains some simple instructions:

Can you beat my super cool rhythm game?

./osu game.beatmap

if you have a recording you can do:

./osu game.beatmap game.recording

When you run the game, you’ll find out it’s a rhythm game in which you click circles that are (roughly) timed with music. You will get a point if you click the circle ‘close enough’ to the right time. The game looks like this:

As mentioned in the README distributed with the challenge, the binary comes with a ‘recording’ playback feature. I intentionally did not distribute a recording, but implemented this feature anyway so that people working on the challenge would have an easy way to test without having to deal with mouse input.

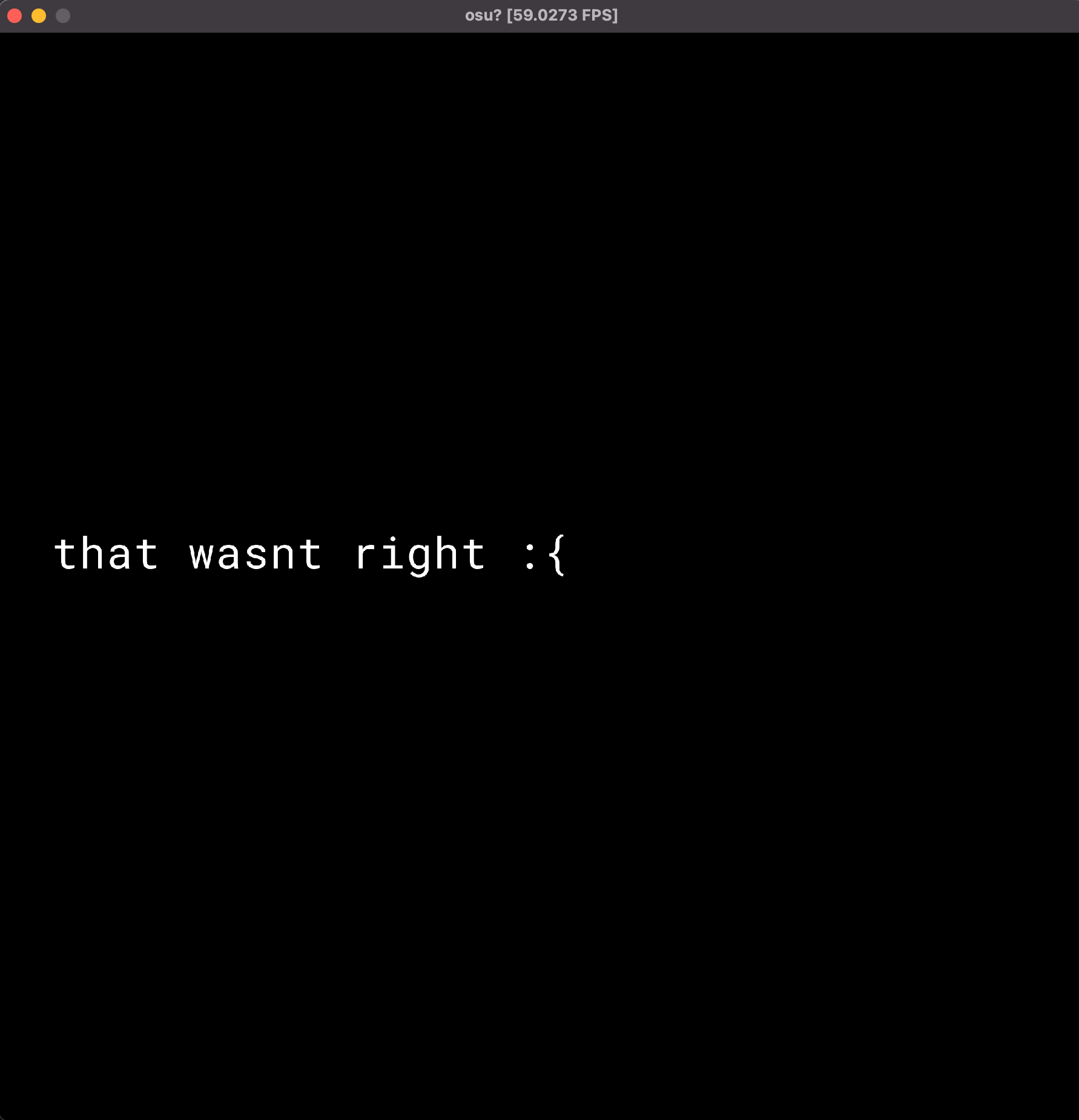

When you allow the game to finish (it takes ~2 minutes), it’ll display a message:

So, it seems we didn’t play the song correctly :(.

Reversing the game logic

Note about debug info

First of all, I think I screwed up in multiple ways w.r.t. debug info in this challenge.

-

The version of the macOS binary that was released did not have debuginfo. This was unintentional, though even with debug info neither Binja nor Ghidra gives me variable names or struct member names either, so I’m not sure this was a huge deal. (You miss out on line numbers, but you still don’t have source.)

-

The Linux binary came with DWARF 5 debug info, which cannot be parsed by Ghidra (and I think also Binja). This was also unintentional. When I decompiled the Linux binary in Binja it looked exactly like the macOS binary (no variable names or struct member names), and I didn’t get any warnings, so I just went with it since I wanted the binaries to match anyway. It turns out (according to a player) that DWARF 5 can be parsed by IDA, so players with a copy of IDA have an unintended advantage.

I released the challenge expecting players to be dealing with what I saw in Binja and Ghidra: symbols, but no variable names or struct members. So that’s what I’ll describe in this writeup, but I’m pretty disappointed that it apparently turned out to be easier with IDA.

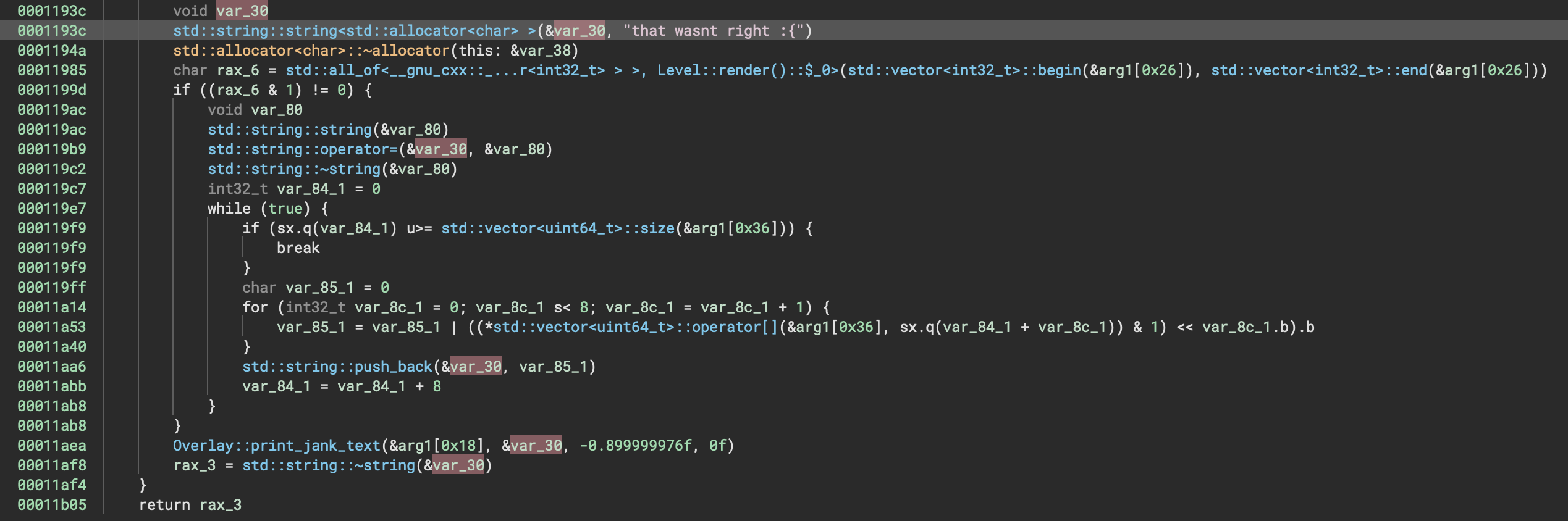

The ‘that wasnt right’ message

The first place to look is at why the game is printing ‘that wasnt right’ after attempting to play the song. I used Binary Ninja, but the decompilation is similar if you use Ghidra. If you look for this string, you’ll find it referenced as part of Level::render:

Level::render is constructing a std::string in var_30 with the contents of the “that wasnt right” message displayed on the screen. There’s some extra logic after this, and if we can enter the if statement, it will replace the string before it finally gets passed to Overlay::print_jank_text.

The high-level goal here (and I apologize if this was unclear) is to get the program into that if statement (at 0x119d), where it will print something other than “that wasnt right”. This was intended to be, at its core, a stereotypical “flag checker”, which either prints the flag or tells you that you’re wrong.

where flag??

So, how do we get into the aforementioned if statement? It’s guarded by:

char rax_6 = std::all_of<__gnu_cxx::_...r<int32_t> > >, Level::render()::$_0>(

std::vector<int32_t>::begin(&level->field_130),

std::vector<int32_t>::end(&level->field_130)

);

if ((rax_6 & 1) != 0) {

// ... interesting stuff happens here...

}

Ew. So &level->field_130 is a vector of int32_t, and we need all of them to… be what, exactly? std::all_of usually accepts a lambda argument that is evaluated on every element in the iterator. We’ll have to dig through some decompiled C++ to find this function. It turns out, std::all_of gets compiled into find_if_not (check if any of the elements of the iterator do not satisfy the condition):

uint64_t std::all_of<__gnu_cxx::__normal_iterator<int32_t*, std::vector<int32_t, std::allocator<int32_t> > >, Level::render()::$_0>(int64_t arg1, int64_t arg2)

{

int64_t var_18 = arg2;

int64_t var_28 = std::find_if_not<__gnu_c...r<int32_t> > >, Level::render()::$_0>(arg1, var_18);

return ((uint64_t)(operator==<int32_t*, int32_t*, std::vector<int32_t> >(&var_18, &var_28) & 1));

}

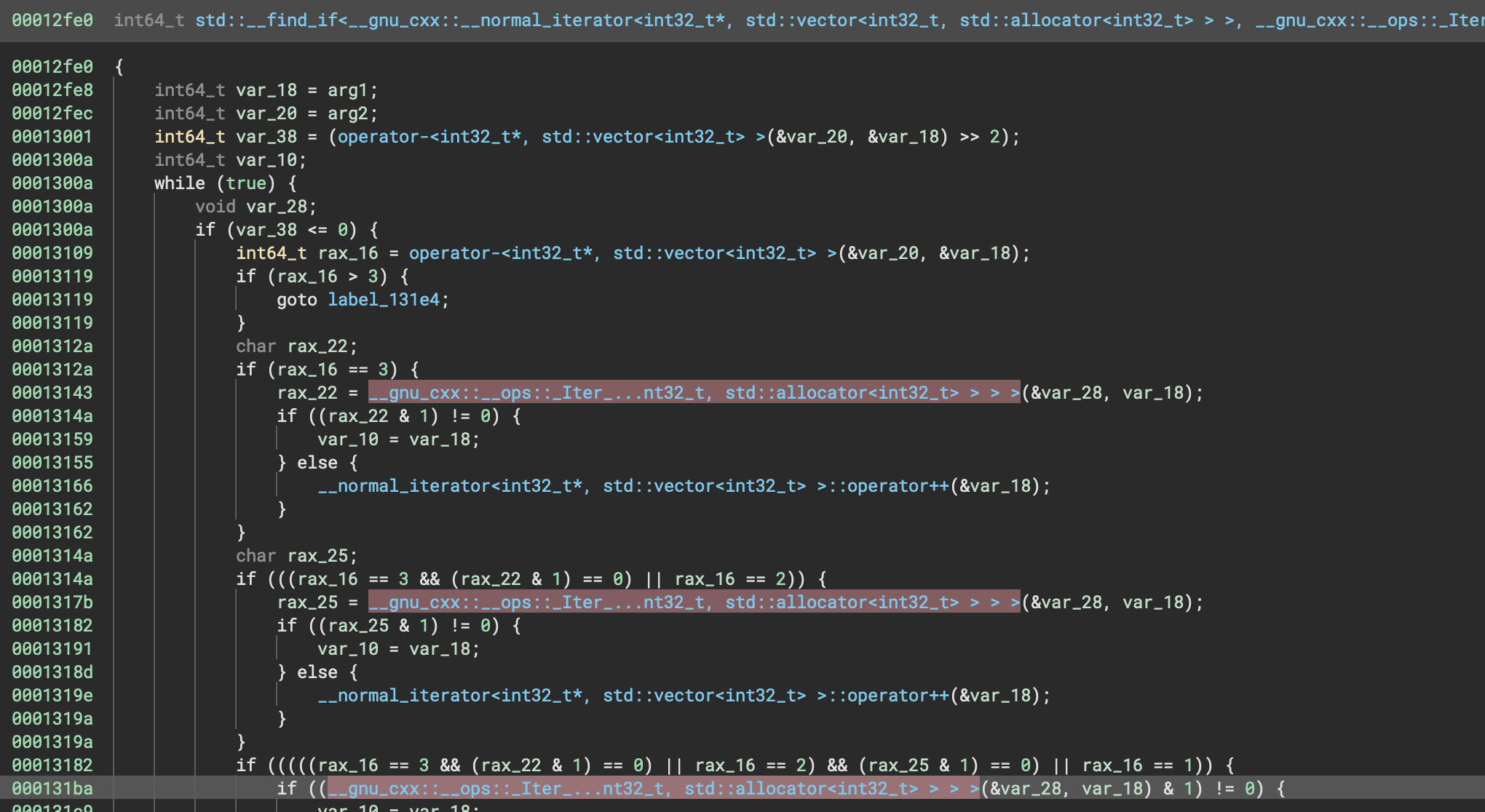

If we dig just a little further, we’ll actually get to this chonky specialization of std::find_if:

The highlighted function is finally what we’ve been waiting for:

uint64_t __gnu_cxx::__ops::_Iter_negate<Level::render()::$_0>::operator()<__gnu_cxx::__normal_iterator<int32_t*, std::vector<int32_t, std::allocator<int32_t> > > >(int64_t arg1, int64_t arg2)

{

int64_t var_10 = arg2;

return (Level::render()::$_0::operator()(

arg1,

*(int32_t*)__normal_iterator<int32_t*, std::vector<int32_t> >::operator*(&var_10) // * (deref)

) ^ 0xff) & 1;

}

Finally, we are calling the lambda, with an element from the vector:

Level::render()::$_0::operator()(

arg1,

*(int32_t*)__normal_iterator<int32_t*, std::vector<int32_t> >::operator*(&var_10) // * (deref)

)

Note it negates the result of the lambda call (with ^ 0xff above) because std::all_of is going to stop if it gets to an element that does not satisfy the condition checked by the lambda.) And what does this lambda check?

uint64_t Level::render()::$_0::operator()(int64_t arg1, int32_t arg2)

{

int64_t var_10 = arg1;

return ((uint64_t)(arg2 == 1 & 1));

}

Whew. All that work, and we find out that in order to avoid the ‘that wasnt right’ message, we need every element of this vector (&level->field_130) to be exactly equal to 1. There might be a plugin that saves some work here, but C++ reversing sucks.

OK – so we’ve reduced the problem to “make every element of &level->field_130 equal 1”.

The ‘beatmap’ format

We ought to take a slight diversion to reverse the input format. When you run the game, you have to pass in a ‘beatmap’ file, which presumably would contain information about how to play the song.

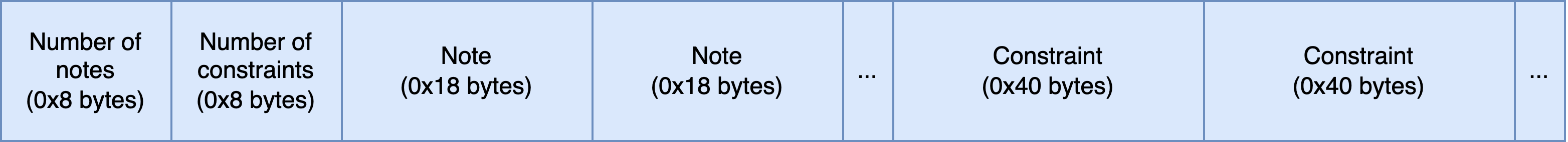

There is a class LevelSave, which is responsible for parsing the beatmap file. You can either reverse the LevelSave::LevelSave constructor statically or just set breakpoints to observe the istream::read calls, but either way, you’d come up with the following format for a beatmap:

From struct member accesses in LevelSave alone, you can infer the member types for the circles stored in the beatmap:

struct StoredCircle {

float field_0;

float field_4;

int64_t field_8;

char field_10;

char field_11;

char field_12;

}

These get placed into various fields in CircleElement, which has conveniently has a lot of named getters, so you can recover the names of CircleElement members:

struct circleelement __packed

{

void** field_0;

int64_t field_8;

float x;

float y;

int64_t field_18;

int64_t field_20;

int64_t entry_tick; // see `Element::should_render`

// and `CircleElement::CircleElement`

int64_t deadline_tick; // see `Element::should_render`,

// `Element::just_died`,

// and `CircleElement::CircleElement`

int32_t score_time; // see `Element::score_time`

int64_t field_40;

int32_t field_48;

int32_t field_4c;

};

and the corresponding format in the file:

struct StoredCircle {

float x;

float y;

int64_t deadline_tick;

char field_10; // it turns out these are r,g,b for the circle color, but it's purely cosmetic

char field_11;

char field_12;

}

After deserializing the circles (the ‘notes’) from the beatmap, each ‘constraint’ from the file is pushed straight to a std::vector<Constraint> without going through a constructor or any additional parsing logic, so you’ll have to look elsewhere to reverse this format. The Level class contains a std::vector<Constraint> at offset 0x160, and there are XREFs in Level::build_index and Level::Level.

Reverse the Level class

After correcting function type signatures to use your partially-reversed Level struct, we know we need to find what logic modifies the vector at offset 0x130 in the Level class (used in the std::all_of from earlier):

std::all_of<__gnu_cxx::_...r<int32_t> > >, Level::render()::$_0>(

std::vector<int32_t>::begin(&level->field_130),

std::vector<int32_t>::end(&level->field_130)

);

If you add this type to the other Level functions, you’ll find this fuction (suspciously named checker) which has a few uses of the same vector:

int64_t Level::checker(struct struct_1* level, int64_t arg2, int64_t arg3)

{

if (level->field_0 > 1) {

arg3 = glad_glGetBufferSubData(0x8c8e, 0, (std::vector<int32_t>::size(&level->field_130) << 2), std::vector<int32_t>::data(&level->field_130));

}

// ...

glad_glBindBuffer(0x8892, ((uint64_t)*(int32_t*)((char*)level + 0x20)));

glad_glVertexAttribIPointer(((uint64_t)*(int32_t*)((char*)level + 0x104)), 1, 0x1404, 4, 0);

glad_glBufferData(0x8892, (std::vector<int32_t>::size(&level->field_130) << 2), std::vector<int32_t>::data(&level->field_130), 0x88e5);

// ...

glad_glBeginTransformFeedback(0);

// ... glDrawArrays call is here

glad_glEndTransformFeedback();

// ...

}

To understand how this vector is used, we need to look at each of these uses:

glad_glGetBufferSubData(0x8c8e, 0, (std::vector<int32_t>::size(&level->field_130) << 2), std::vector<int32_t>::data(&level->field_130));

First, the size and a pointer to this vector’s data are passed to glGetBufferSubData. It looks like the first argument is some sort of enum. You can Google for opengl headers "0x8c8e" and you’ll find this header containing the definition. It looks like 0x8c8e is GL_TRANSFORM_FEEDBACK_BUFFER.

From the OpenGL Wiki:

Transform Feedback is the process of capturing Primitives generated by the Vertex Processing step(s), recording data from those primitives into Buffer Objects. This allows one to preserve the post-transform rendering state of an object and resubmit this data multiple times.

In other words, Transform Feedback is one way of capturing the output of vertex shaders, and allowing it to be copied back to the CPU. glGetBufferSubData is one function that can be used for this copy.

Next, we see this vector also used in glad_glBufferData. glad_glVertexAttribIPointer is used to specify the layout of ‘vertex data’, so that it can be mapped to input variables in an OpenGL shader.

glad_glVertexAttribIPointer(((uint64_t)level->field_104), 1, 0x1404, 4, 0);

glad_glBufferData(0x8892, (std::vector<int32_t>::size(&level->field_130) << 2), std::vector<int32_t>::data(&level->field_130), 0x88e5);

So what we have is that this vector (which needs to all be 1’s), is both an input and output of a GPU shader.

Reversing the Shader

Now, we know that the flag checker logic is actually implemented in an OpenGL shader. Let’s try to find that shader. Turns out it’s not that hard, since Level::checker calls Shader::activate(&*(int64_t*)((char*)level + 0xfc), arg2, arg3);. After labeling some struct fields, we find a call to the Shader constructor, from the Level constructor:

Shader::Shader(&arg1->checker_shader, checker_vertex_shader_text, 0, 1);

and checker_vertex_shader_text is a global containing the code for a OpenGL shader. At the top, we find a list of inputs and outputs of the shader.

#version 150

in ivec4 r;

in uvec4 code[2];

in int s;

ivec4 r_c;

int s_c;

int t;

out int out_attr;

out vec4 color;

And looking at main…

void main()

{

r_c = r;

s_c = s;

uint count = 0u;

uint pc = 0u;

while (count < 10000u && pc < 32u) {

uint insn = fetch_insn(pc);

pc = handle_insn(insn, pc);

count += 1u;

}

out_attr = s_c;

color = vec4(0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 1.0);

gl_Position = vec4(0, 0, 0, 0);

}

Oh no, it’s a VM! But luckily, there are function names and a few useful variable names. Notably, s_c is initialized to s (an input to the shader), and at the end is transferred to out_attr, the only meaningful output of the shader. But we still need to figure out what the other inputs and outputs of this shader are.

But after adding to our Level struct, things aren’t looking too bad:

We can infer that the s input to the shader corresponds to the field_130 vector we found earlier (the one that must be filled with all-1s):

// Level::checker

// s is a integer, and the element for each shader is 4 bytes apart (no padding)

glad_glVertexAttribIPointer(((uint64_t)level->s_attr), 1, 0x1404, 4, 0);

glad_glBufferData(0x8892, (std::vector<int32_t>::size(&level->field_130) << 2), std::vector<int32_t>::data(&level->field_130), 0x88e5);

// Level::setup

arg1->s_attr = Shader::attrib(&arg1->checker_shader, "s")

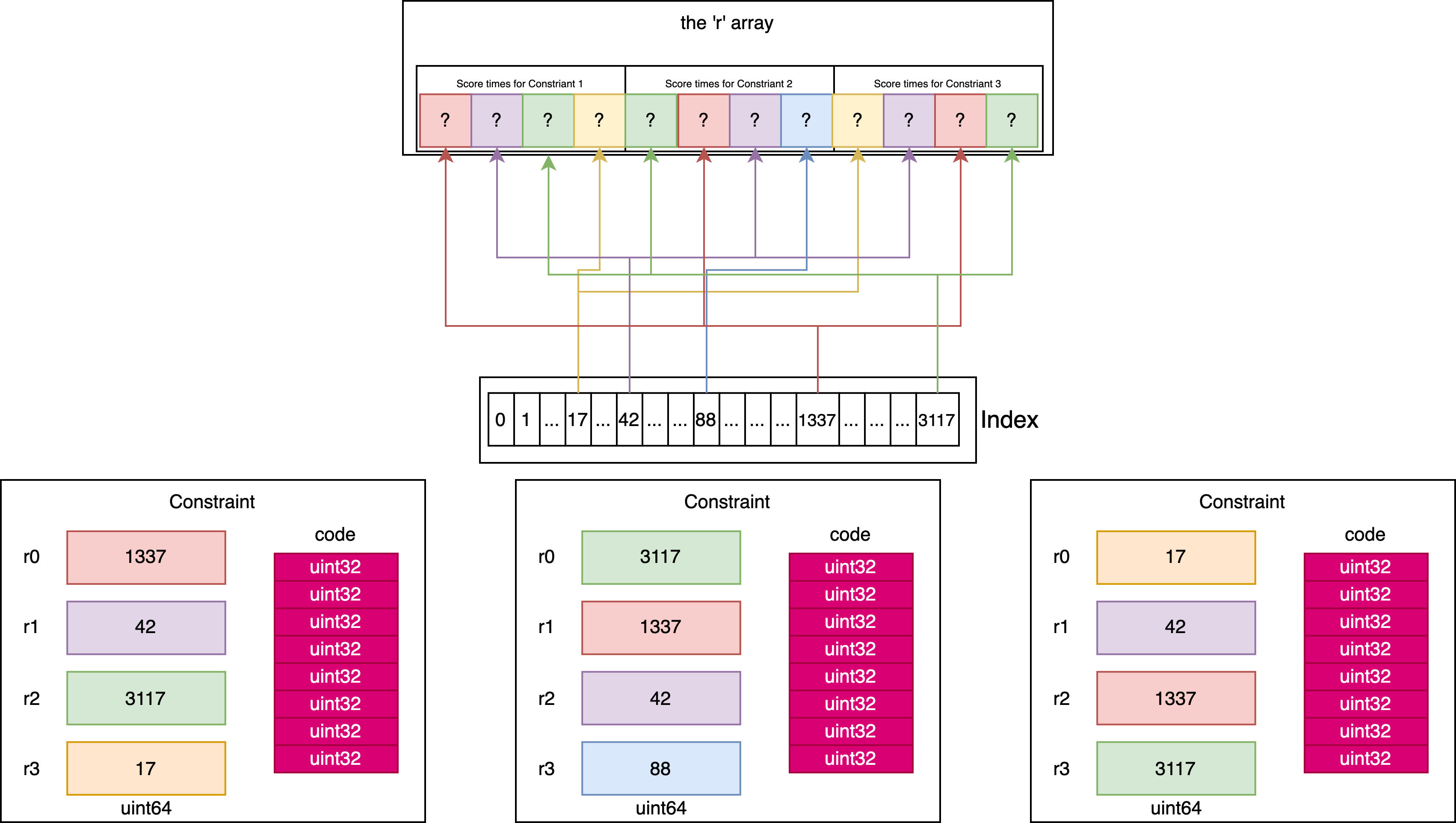

Similarly, we can conclude that the vector at offset 0x148 in the Level struct is the r input:

// Level::checker

// r is a vector of 4 integers, and the vector for each shader is 0x10 bytes apart (no padding)

glad_glVertexAttribIPointer(zx.q(arg1->r_attr), 4, 0x1404, 0x10, 0)

glad_glBufferData(0x8892, std::vector<int32_t>::size(&arg1->field_148) << 2, std::vector<int32_t>::data(&arg1->field_148), 0x88e5)

// Level::setup

arg1->r_attr = Shader::attrib(&arg1->checker_shader, "r")

and the vector at offset 0x118 is the code input.

// Level::checker

glad_glBindBuffer(0x8892, zx.q(arg1->code_buf_num))

// This configures code[0] to be bytes 0x0-0x10 (plus 0x20 * index for every shader invocation)

glad_glVertexAttribIPointer(zx.q(arg1->code_attr), 4, 0x1405, 0x20, 0)

// This configures code[1] to be bytes 0x10-0x20 (plus 0x20 * index for every shader invocation)

glad_glVertexAttribIPointer(zx.q(arg1->code_attr_plus_1), 4, 0x1405, 0x20, 0x10)

// Level::setup

arg1->code_attr = Shader::attrib(&arg1->__offset(0xfc).q, "code", rdx_11)

arg1->code_attr_plus_1 = arg1->code_attr + 1

...

glad_glBindBuffer(0x8892, zx.q(arg1->code_buf_num))

glad_glBufferData(0x8892, std::vector<uint32_t>::size(&arg1->field_118) << 2, std::vector<uint32_t>::data(&arg1->field_118), 0x88e6)

Renames:

&arg1->field_130->&arg1->s_vec&arg1->field_148->&arg1->r_vec&arg1->field_118->&arg1->code_vec

Reversing the Constraint format

Level::Level inserts into code_vec using the elements at offset 0x20 thru 0x40 of each Constraint. (variable names added by me)

int64_t constraints_begin = std::vector<Constraint>::begin(&arg1->constraints)

int64_t constraints_end = std::vector<Constraint>::end(&arg1->constraints)

while (true) {

if ((std::operator!=<Constraint*>(&constraints_begin, &constraints_end) & 1) == 0) {

break

}

void* cur = std::__wrap_iter<Constraint*>::operator*(&constraints_begin)

int64_t cur_end = std::vector<uint32_t>::end(&arg1->constraint_subdata)

uint32_t* cur_end_iter

std::__wrap_iter<uint32_t const*>::__wrap_iter<uint32_t*>(&cur_end_iter, &cur_end)

int64_t var_b0_1 = std::vector<uint32_t>::insert<uint32_t*>(&arg1->constraint_subdata, cur_end_iter, cur + 0x20, cur + 0x40)

std::__wrap_iter<Constraint*>::operator++(&constraints_begin)

}

Looking at XREFs to r_vec, we see it’s used in Level::handle_click, after we’ve found the circle that covers the click.

// The circle got clicked, so it is either marked as scoring or not (if too early/late)

Element<GLCircleElementInfo>::kill(cur_circle)

int64_t circ_idx = sx.q(i)

// Use the index of the circle in a map of vector<uin64_t>

int64_t r_vec_indices = std::map<uint64_t, std::vector<uint64_t> >::operator[](&arg1->index, i: &circ_idx)

// Iterate over each index `rax_16` in r_vec_indices, setting

// r_vector[rax_16] = Element::score_time(cur_curcle)

int64_t c_indices_begin = std::vector<uint64_t>::begin(r_vec_indices)

int64_t c_indices_end = std::vector<uint64_t>::end(r_vec_indices)

while (true) {

if ((std::operator!=<uint64_t*>(&c_indices_begin, &c_indices_end) & 1) == 0) {

break

}

int64_t rax_16 = *std::__wrap_iter<uint64_t*>::operator*(&c_indices_begin)

// Update `r_vector` with the score_time for the circle that was just clicked

*std::vector<int32_t>::operator[](&arg1->r_vector, rax_16) = Element<GLCircleElementInfo>::score_time(cur_circle)

std::__wrap_iter<uint64_t*>::operator++(&c_indices_begin)

}

Here they look up the std::vector in the index corresponding to the circle that was clicked on. They then update each of these indices in r_vector accordingly.

But how did level->index get built? Level::build_index uses uint64_ts at offsets 0x0, 0x8, 0x10, and 0x18 in each constraint. An insertion is made into the index for each of these uint64_ts. The index can be used to lookup all occurances of a particular uint64_t within all of the constraints. The first constraint will insert values [0, 4) into the index, and the second constraint will insert [4, 7), and so on. So you can locate exacty which constraints mention one of of these uint64_ts, and which of the four offsets they appear at in those constraints. (some variable names added by me)

uint64_t Level::build_index(struct level* arg1)

{

int32_t var_14 = 0;

int64_t var_28 = std::vector<Constraint>::begin(&arg1->constraints);

int64_t var_30 = std::vector<Constraint>::end(&arg1->constraints);

uint64_t rax_4;

while (true) {

rax_4 = std::operator!=<Constraint*>(&var_28, &var_30);

if ((rax_4 & 1) == 0) {

break;

}

void* rax_5 = std::__wrap_iter<Constraint*>::operator*(&var_28);

void* start_addr = rax_5;

for (void* end_addr = ((char*)rax_5 + 0x20); start_addr != end_addr; start_addr = ((char*)start_addr + 8)) {

int64_t var_58 = *(int64_t*)start_addr;

int64_t var_60 = ((int64_t)var_14);

std::vector<uint64_t>::push_back(std::map<uint64_t, std::vector<uint64_t> >::operator[](&arg1->index, &var_58), &var_60);

var_14 = (var_14 + 1);

}

std::__wrap_iter<Constraint*>::operator++(&var_28);

}

return rax_4;

}

So we can finally fill in the format for a constraint:

struct Constraint {

uint64_t circle_ids[4];

uint32_t code[8];

}

Putting the pieces together

- Each shader invocation corresponds to a single Constraint

- The ‘r’ ivec4 for each Constraint is filled with the ‘score_time’ for four specific circles, and will get updated when you correctly click circles in the game.

- The ‘index’ allows for quickly looking up a list of indices in the

r_vectorwhich need to be updated when a circle is clicked.

The virtual machine

Summary of the VM input/output

We now fully understand the virtual machine:

- For a particular invocation of the shader, the

codevector will hold the code that came from the Constraint in the beatmap file, andrwill contain a list of tick numbers for the tick at which specific circles corresponding to that constraint were clicked (or-1if not clicked yet or clicked incorrectly). Thisrvector is kept up-to-date inhandle_clickusing the index. - The

svector is copied to/from thestatevector in the application every timecheckeris called (every frame). The virtual machine can write to this and use it in future invocations. - At the end of the game, every position of the state vector needs to be equal to ‘1’ for the game to print something other than ‘that wasnt right’.

Writing a disassembler

First we need to parse the beatmap file, which was reversed earlier.

with open("../dist-osu/game.beatmap", "rb") as f:

data = f.read()

note_count, constraint_count = struct.unpack("<QQ", data[:16])

constraints = data[16+24*note_count:]

# Read the constraints in

code_examples = set()

for x in range(0, len(constraints), 64):

constraint = constraints[x:x+64]

decoded = list(struct.unpack("<4Q32s", constraint))

circle_list, code = decoded[:4], decoded[4]

code_examples.add(code)

It turns out there are only 6 different programs!

>> len(code_examples)

6

Writing a disassembler is as simple as copying from handle_insn in the shader. You can find my disassembler here.

Reversing the constraints

Now we can look at the programs that are executing in the shader. Remember that the goal is for state == 1 at the end of every program.

Type 1: Cardinality

b'\x87\x86\xaf\xa6\xd7\xc6\xa0\xe6\xd8\x86\xf6\xf8\xe6\x9f\xf6\xc4~n\x80\x80\x80\x80\x80\x80\x80\x80\x80\x80\x80\x80\x80\x80'

[0x0] temp = r0 < 0

[0x1] r0 = temp

[0x2] temp = r1 < 0

[0x3] r1 = temp

[0x4] temp = r2 < 0

[0x5] r2 = temp

[0x6] temp = r0 + r1

[0x7] r3 = temp

[0x8] temp = r3 + r2

[0x9] r0 = temp

[0xa] r3 = 0x1

[0xb] temp = r3 + r3

[0xc] r3 = temp

[0xd] temp = r3 < r0

[0xe] r3 = 0x1

[0xf] jz temp, 0x11

[0x10] r3 = 0xffffffff

[0x11] xchg r3, state

This constraint counts the number of [r0, r1, r2] which are less than zero, and places that count in r0 (instructions 0x0-0x9). Because r0, r1, and r2 are the tick number at which three notes were scored (or -1 if not scored), this is counting the number of notes (out of these three) that were not successfully scored.

Then, it sets r3 = 2 (by setting r3 = 1 and then doubling it), and then compares the count (in r0) with r3 (instruction 0xd). It sets state to 0xffffffff if r3 < r0, and 1 otherwise. This means that at most 2 of the circles specified by this constraint can be not scored.

3 of the other 5 constraints are actually nearly identical to this one.

b'\x87\x86\xaf\xa6\xd7\xc6\xa0\xe6\xd8\x86\xf6\x9f\xf6\xc4~n\x80...'- at most 1 of the circles specified by this constraint can be not scored.b'\x87\x86\xaf\xa6\xd7\xc6\xa0\xe6\xd8\x86\xf6\xe7\xf6\xc4~n\x80...'- at least 1 of the circles specified by this constraint must be not scoredb'\x87\x86\xaf\xa6\xd7\xc6\xa0\xe6\xd8\x86\xf6\xf8\xe6\xe7\xf6\xc4~n\x80...'- at least 2 of the circles specified by this constraint must be not scored.

Note that this constraint doesn’t specify anything about the order in which notes are clicked. It only specifies which notes should be scoring and which should not.

Type 2: Ordering (strong)

b'\xf6\x87\xed\xaf\xdd\xd7\xcd\x81\xc4~\xa7\xdc\xcf\xcc\x81\xc4~n\x80...'

[0x0] r3 = 0x1

[0x1] temp = r0 < 0

[0x2] jnz temp, 0x9

[0x3] temp = r1 < 0

[0x4] jnz temp, 0x9

[0x5] temp = r2 < 0

[0x6] jnz temp, 0x9

[0x7] temp = r0 - r0

[0x8] jz temp, 0xa

[0x9] r3 = 0xffffffff

[0xa] temp = r0 < r1

[0xb] jz temp, 0x10

[0xc] temp = r1 < r2

[0xd] jz temp, 0x10

[0xe] temp = r0 - r0

[0xf] jz temp, 0x11

[0x10] r3 = 0xffffffff

[0x11] xchg r3, state

In this program, there are two opportunities for failure: 0x9 and 0x10. If you avoid both of these, state will be set to 1. The first failure point corresponds to checking to make sure that all of the notes for this constraint are scored. If any of them are not scored, state will be set to 0xffffffff. Note that at the beginning of the game, no notes could possibly be scored, so this constraint cannot be satisifed until much later in the game (all constraint are re-evaluated on every frame).

The second failure point corresponds to whether either of r0 < r1 or r1 < r2 are violated. This program is making a requirement about the order that you select notes in.

Type 3: Ordering (weak)

b'n\xff\xe5\xf6\xaf\xd5\x87\xc4~\xd7\xd5\xaf\xc4~n\x80...'

[0x0] xchg r3, state

[0x1] temp = r3 < 0

[0x2] jnz temp, 0x8

[0x3] r3 = 0x1

[0x4] temp = r1 < 0

[0x5] jnz temp, 0x9

[0x6] temp = r0 < 0

[0x7] jz temp, 0x9

[0x8] r3 = 0xffffffff

[0x9] temp = r2 < 0

[0xa] jnz temp, 0xe

[0xb] temp = r1 < 0

[0xc] jz temp, 0xe

[0xd] r3 = 0xffffffff

[0xe] xchg r3, state

Similar to Type 2, there are two failure points here (0x8 and 0xd). However it is important to note that unlike Type 2, we check the original value of state, and if its less than 0 then we immediately jump to a failure point. This means that a failure of this type of constraint is permanent: a failure on any frame will mean this constraint will never be satisfied.

There are two other paths to a failure:

r1 >= 0andr0 < 0r2 >= 0andr1 < 0

To understand this constraint, you have to remember that this is executed on every frame. This constraint will fail if r1 is scored but r0 is not, or if r2 is scored but r1 is not.

This is a constraint on the order that notes are clicked if they are clicked. Another way of writing it is:

- Circle 2 scored => (Circle 1 scored and Circle 1 scored before Circle 2)

- AND Circle 1 scored => (Circle 0 scored and Circle 0 scored before Circle 1)

Writing a solver

Now we know exactly what each of the 6 programs do, and we just have to translate them into constraints. This was designed to be difficult to encode into SMT. I don’t think encoding any part of the problem as a bitvector will result in a tractable problem for a SMT solver. However, this problem can be easily solved (by a SAT or SMT solver) if encoded into boolean logic.

Where flag?? pt. 2

The goal this entire time has been to get the state vector to be all 1s so that we can pass the check in Level::render and get some message other than ‘That wasnt right’. But what will it print if we can pass that check?

From Level::render (variable names mine):

void new_string

std::string::string(&new_string)

std::string::operator=(&string_to_print, &new_string)

std::string::~string(&new_string)

int32_t outer_idx = 0

while (true) {

if (sx.q(outer_idx) u>= std::vector<uint64_t>::size(&level->field_1b0)) {

break

}

char var_85_1 = 0

for (int32_t inner_index = 0; inner_index s< 8; inner_index = inner_index + 1) {

var_85_1 = var_85_1 | ((*std::vector<uint64_t>::operator[](&level->field_1b0, sx.q(outer_idx + inner_index)) & 1) << inner_index.b).b

}

std::string::push_back(&string_to_print, var_85_1)

outer_idx = outer_idx + 8

}

This iterates over every 8 elements of &level->field_1b0 (a std::vector<uint64_t>), and takes the low bit from each to form a byte of the new string. Look for XREFs on this field and you’ll find one in Level::handle_click:

rax_4 = Element<GLCircleElementInfo>::score_time(rax_5)

if (rax_4.d != 0xffffffff) {

int64_t var_78 = Element<GLCircleElementInfo>::id(rax_5)

rax_4 = std::vector<uint64_t>::push_back(&arg1->field_1b0, &var_78)

}

Every time a note is clicked (and successfully scored) it pushes the id of that note into &arg1->field_1b0!! Trace around the XREFs for this id field, and you’ll find it’s just the index of the note in the original beatmap file.

Encode the constraints into SAT

I chose to encode the constraints into SAT, though I know the only solver of this challenge had a somewhat different SMT encoding.

In SAT, every clause (at least, in conjunctive-normal-form (CNF) used by solvers) consists of a list of variables that are OR-ed together. For a formula to be satisfied, every clause must be satisified. (Thus, at least one variable from every clause must be set to true.)

I used the pysat library, which provides a few nice utilities and a python interface for interacting with various solvers. The solver I used is called ‘cadical’.

Implicit constraints & creating variables

There are a few constraints besides those in the VM that you needed to discover while reversing or playing the game. Some of these are obvious, but are important to encode explicitly into the SAT formula.

- Every note can only be clicked once

- You can only click one note per tick

- You cannot click a note in two consecutive ticks (see

Level::handle_click, which requires that in the previous frame, the mouse button was not pressed) - Notes can only score within 30 ticks of their deadline (see

Element::kill)

To get the flag, we need to know which notes are scored and in what order to click them. For each note, we will make a variable for each of the 30 options.

Pysat comes with a built-in CardEnc utility class which can generate optimal encodings of ‘at most N’ or ‘at least N’ cardinality constraints. We will use these to assert that each note can be scored on at most 1 of the thirty ticks.

def create_base_constraints(notes):

options_for_note = []

constraints = []

max_tick = max([n for n in notes])

# Here we create a variable for each of the 30 ticks a note could be scored on

SCORE_THRESHOLD = 30

for tick_due in notes:

options = {i: pool.id() for i in range(tick_due-SCORE_THRESHOLD, tick_due-1)}

# A note can only be clicked once!

constraints += CardEnc.atmost(list(options.values()), 1, vpool=pool)

options_for_note.append(options)

# Now, for every tick, check at most one note is clicked

is_tick_free = []

for i in range(max_tick):

vs = []

this_tick_free = pool.id()

is_tick_free.append(this_tick_free)

for o in options_for_note:

if i in o:

vs.append(o[i])

# this_tick_free will be forced false if any are used on this tick

constraints += CardEnc.atmost(vs + [this_tick_free], 1, vpool=pool)

# Now we enforce that we don't select something two frames in a row

# (this is a limitation of the handle_click function)

for i in range(1, max_tick):

prev = is_tick_free[i-1]

cur = is_tick_free[i]

constraints += [[prev, cur]] # at least one of them must be free

return constraints, options_for_note

Encoding each of the VM constraints into SAT

Since we earlier reversed each of the programs, we now just have to encode them into SAT. The cardinality constraints are easy, thanks to the CardEnc pysat utility class.

# This gets the list of 30 variables for each note (the 30 options for when a note can be clicked)

# and combines them into one list.

#

# The idea here is that instead of saying 'at least one of these notes must score' we can say

# 'at least one of these 90 variables must be true'. Thanks to the other constraints, we do

# not have to worry about notes being played multiple times or multiple notes being played

# during the same tick.

def get_combined_var_list(circle_list):

combined_vars = []

# only the first three notes in the list are ever referenced by the programs

for c in circle_list[:3]:

combined_vars.extend(options_for_note[c].values())

return combined_vars

# For each of the 4 cardinality constraints, translate them into

# "At [least|most] N **scored**" instead of "At [least|most] N **not scored**

# and then encode using pysat's CardEnc

if b'\x87\x86\xaf\xa6\xd7\xc6\xa0\xe6\xd8\x86\xf6\xf8\xe6\x9f\xf6\xc4~n\x80' in code:

# At most 2 NOT scored <=> At least 1 scored

combined_vars = get_combined_var_list(circle_list)

sat_constraints += CardEnc.atleast(combined_vars, 1, vpool=pool)

elif b'\x87\x86\xaf\xa6\xd7\xc6\xa0\xe6\xd8\x86\xf6\x9f\xf6\xc4~n\x80' in code:

# At most 1 NOT scored <=> At least 2 scored

combined_vars = get_combined_var_list(circle_list)

sat_constraints += CardEnc.atleast(combined_vars, 2, vpool=pool)

elif b'\x87\x86\xaf\xa6\xd7\xc6\xa0\xe6\xd8\x86\xf6\xe7\xf6\xc4~n\x80' in code:

# At least 1 NOT scored <=> At most 2 scored

combined_vars = get_combined_var_list(circle_list)

sat_constraints += CardEnc.atmost(combined_vars, 2, vpool=pool)

elif b'\x87\x86\xaf\xa6\xd7\xc6\xa0\xe6\xd8\x86\xf6\xf8\xe6\xe7\xf6\xc4~n\x80' in code:

# At least 2 NOT scored <=> At most 1 scored

combined_vars = get_combined_var_list(circle_list)

sat_constraints += CardEnc.atmost(combined_vars, 1, vpool=pool)

The other two constraints (that constrain ordering) are somewhat more difficult.

# Create SAT constraints to represent b => (a AND a < b)

def add_sat_lt_half_implication(a, b):

a_options = options_for_note[a] # all 30 options for when this note can be played

b_options = options_for_note[b]

cons = []

for o1, v in a_options.items():

# Suppose a is at o1

# then b cannot be < o1

lte_options = [v2 for x, v2 in b_options.items() if x <= o1]

# If a is at o1 (v true), then x (b is at some location < o1) is forced false

cons += [[-v, -x] for x in lte_options]

for o1, v in b_options.items():

# Suppose b is at o1

# then a must be < o1

gt_options = [v2 for x, v2 in a_options.items() if x < o1]

# If b is at o1 (v true), then one of the gt_options (a is at some location < o1) must be true

cons.append([-v] + gt_options)

return cons

# And then we call the above function on both a < b and b < c

# ...

elif b'n\xff\xe5\xf6\xaf\xd5\x87\xc4~\xd7\xd5\xaf\xc4~n\x80' in code:

# c => (b ^ (b < c))

# b => (a ^ (a < b))

sat_constraints += add_sat_lt_half_implication(circle_list[0], circle_list[1])

sat_constraints += add_sat_lt_half_implication(circle_list[1], circle_list[2])

# ...

Lastly,

# Create SAT constraints to represent a < b where both a and b are actually scored

def add_sat_lt_included(a, b):

a_options = options_for_note[a]

b_options = options_for_note[b]

cons = []

for o1, v in a_options.items():

# Suppose a is at o1

# then b must be > o1

gt_options = [v2 for x, v2 in b_options.items() if x > o1]

cons.append([-v] + gt_options)

for o1, v in b_options.items():

# Suppose b is at o1

# then a must be < o1

gt_options = [v2 for x, v2 in a_options.items() if x < o1]

cons.append([-v] + gt_options)

return cons

# And then we call the above function on both a < b and b < c

# ...

elif b'\xf6\x87\xed\xaf\xdd\xd7\xcd\x81\xc4~\xa7\xdc\xcf\xcc\x81\xc4~n\x80' in code:

# a < b < c, all are scored

for c in circle_list:

sat_constraints += [list(options_for_note[c].values())] # at least one of them!

sat_constraints += add_sat_lt_included(circle_list[0], circle_list[1])

sat_constraints += add_sat_lt_included(circle_list[1], circle_list[2])

Now that we have all the constraints encoded into SAT, we can run the solver, and decode the message that would be displayed.

# We have a SAT problem, solve it

solver = Solver('cadical', bootstrap_with=sat_constraints)

assert solver.solve()

soln = solver.get_model()

# Look at all the variables in the solution and create a 'replay'

# A 'replay' describes what note to play on each tick (-1 = play nothing)

replay = [-1 for _ in range(max([n for n in notes_new]))] # one spot for each tick

for i, n in enumerate(notes_new):

options = options_for_note[i]

for o, var in options.items():

if soln[var-1] > 0: # if true in the SAT assignment, that note was played on this tick

assert replay[o] == -1

replay[o] = i

# The flag is decoded from the low bit of the note ids played

bits = []

for r in replay:

if r != -1:

bits.append(r & 1)

answer = []

for i in range(0, len(bits), 8):

num = 0

for z in range(8):

num |= (bits[i+z] << z)

answer.append(num)

flag = bytes(answer)

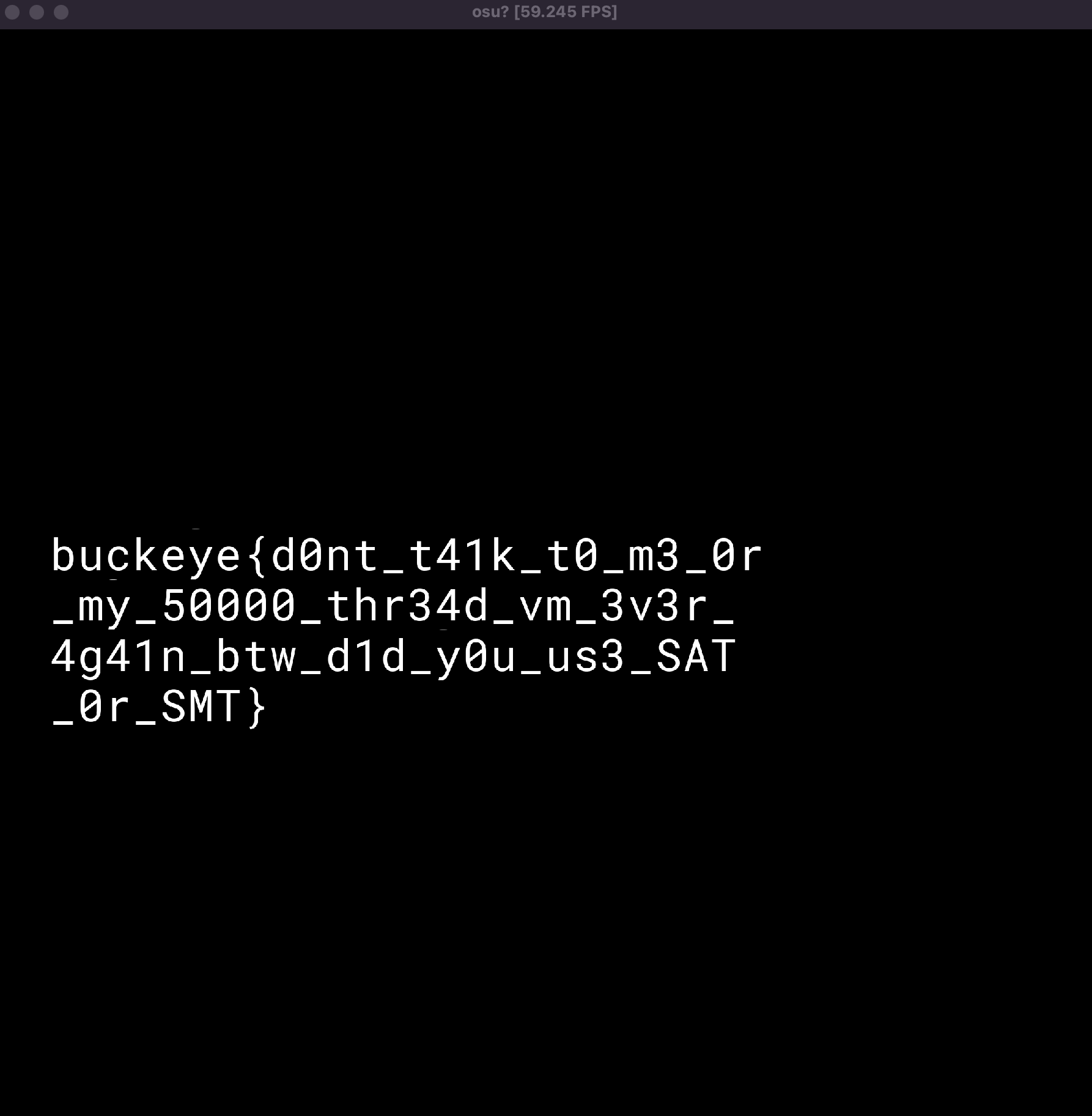

Run the final solve script and you get the flag:

buckeye{d0nt_t41k_t0_m3_0r_my_50000_thr34d_vm_3v3r_4g41n_btw_d1d_y0u_us3_SAT_0r_SMT}

You can also assemble a replay (see the Recording class in the game), and run it to see the flag:

# Encode the replay

replay_bytes = struct.pack("<Q", len(replay))

for r in replay:

replay_bytes += struct.pack("<q", r)

with open("replay", "wb") as f:

f.write(replay_bytes)